Founders mix these up all the time.

Someone says “let’s build an MVP,” but what they really need is a prototype to test the flow. Or they build a proof of concept to prove the tech works, then treat it like market validation and wonder why users don’t stick.

The problem is these three things live in the same early-stage zone, so they sound interchangeable in meetings. They are not. The difference between prototype vs MVP and proof of concept vs MVP isn’t just terminology. Each one answers a different question, attracts a different kind of feedback, and leads to very different build decisions.

This guide breaks down MVP vs prototype vs proof of concept in plain terms, with a simple way to choose the right one based on what you need to learn first. By the end, you’ll know exactly what to build next and what success should look like for that stage.

A prototype helps you test whether the idea and flow make sense. A proof of concept helps you confirm that the risky technical part can work. An MVP helps you prove real user adoption through actual usage and measurable behavior. Choose based on what you need to learn first, such as market behavior, user experience, or technical risk.

The Core Difference in One Line Each

These three deliverables happen early, but they’re built for different kinds of uncertainty. If you use the wrong one, you either collect the wrong feedback or spend time building things that cannot answer your biggest question.

Here are the simplest one-line definitions you can use to keep your team aligned.

- Prototype: A quick model of a product used to test the idea, flow, and user understanding before building full functionality.

- Proof of concept: A small technical experiment used to confirm that a risky feature or integration is feasible in real conditions.

- MVP: A minimal usable version of a product released to real users to measure adoption and learn what to build next.

MVP vs Prototype vs Proof of Concept at a Glance

Founders often pick the wrong approach because they judge progress by how “real” something looks.

A prototype can look polished and still tell you nothing about adoption.

A proof of concept can work perfectly and still have no market pull.

The fastest way to avoid that trap is to compare them side by side based on what each one is meant to prove. This quick view of MVP vs prototype vs proof of concept makes it easier to choose the right next step and measure the right outcome.

| Type | Primary Goal | What You Build | Who Uses It | Success Looks Like | Typical Mistake |

| Prototype | Test the idea and flow | Clickable screens or a simple demo | You and early testers | People understand it and can complete the flow | Treating positive reactions as validation |

| Proof of Concept | Prove technical feasibility | A technical experiment around one risky part | Mostly engineers | The risky part works under realistic conditions | Expanding it into a mini product |

| MVP | Prove adoption through usage | One usable workflow end-to-end | Real users | Users complete the core action and return | Stuffing in extra features to feel complete |

If you are still unsure which one to start with, focus on the biggest unknown. When the main risk is whether users understand the flow, a prototype gives you fast clarity. When the main risk is whether the tech can actually work, a proof of concept reduces engineering uncertainty. When the main risk is whether people will adopt it, turning opinions into measurable behavior is the whole point of an MVP.

When You Need a Prototype

A prototype is the right move when your biggest risk is clarity. You are not trying to prove the market yet, and you are not trying to solve hard engineering problems yet. You are trying to see whether users understand the idea and whether the flow feels natural before you invest in building the real thing. This is also where many teams confuse what is a prototype with an MVP, and end up measuring the wrong outcomes.

Use a Prototype When the Risk is Understanding

A prototype is useful when you are still answering questions like:

- Do users understand what this does within seconds?

- Can they find the next step without help?

- Does the workflow match how they already think?

- Which version of the flow creates less confusion?

What to Include in a Prototype

Keep it lightweight. Your goal is speed and learning.

- Key screens only

- Clickable flow that shows the main journey

- Simple copy that explains the promise

- Enough detail to test comprehension

What Success Looks Like

You are looking for clarity, not compliments.

- Users complete the flow without being guided

- They can explain the value back in their own words

- They choose the same path consistently instead of hesitating

When You Need a Proof of Concept

A proof of concept is the right move when the biggest risk is technical. The question is not whether users will like the idea. The question is whether the hardest part can actually work in real conditions. This stage saves you from building a full product around a technical assumption that later breaks, and it clears up confusion around MVP vs PoC.

Use a Proof of Concept When the Risk is Feasibility

A proof of concept helps when you are trying to answer questions like:

- Can this integration work with the systems we must support?

- Can we hit the performance target without cutting key functionality?

- Can we handle the data format, volume, and edge cases reliably?

- Can we meet security and compliance expectations for this use case?

What to Include in a Proof of Concept

Keep it narrow and ruthless. Focus on the riskiest piece.

- One technical experiment, not a product

- Realistic data or realistic load tests

- Basic logging to see what fails and why

- Notes on constraints and what would be required to productionize

What Success Looks Like

Success means confidence in feasibility and clearer effort estimates.

- The risky part works under realistic conditions

- Known failure points are documented

- The next build steps are clear and scoped

When You Need an MVP

An MVP is the right move when the biggest risk is adoption. You are past the stage of testing whether the idea sounds good. Now you need to see whether real users will actually use it, return to it, and treat it like a solution instead of a demo. This is the key distinction in MVP vs prototype vs proof of concept because only an MVP is built to test user pull-through real usage.

Use an MVP When the Risk is Demand

An MVP helps when you are trying to answer questions like:

- Will users complete the core action without you guiding them?

- Will they come back within a week or two?

- Will they invite others or ask for access again?

- Will they show clear intent to pay or upgrade?

What to Include in an MVP

Keep it small, but usable. The goal is real behavior.

- One workflow end-to-end

- A simple onboarding path

- Basic tracking for the core action

- Enough reliability to avoid breaking trust early

What Success Looks Like

Success is not compliments. Success is behavior you can measure.

- Users complete the main task

- They return without reminders

- The product creates a repeatable habit or workflow

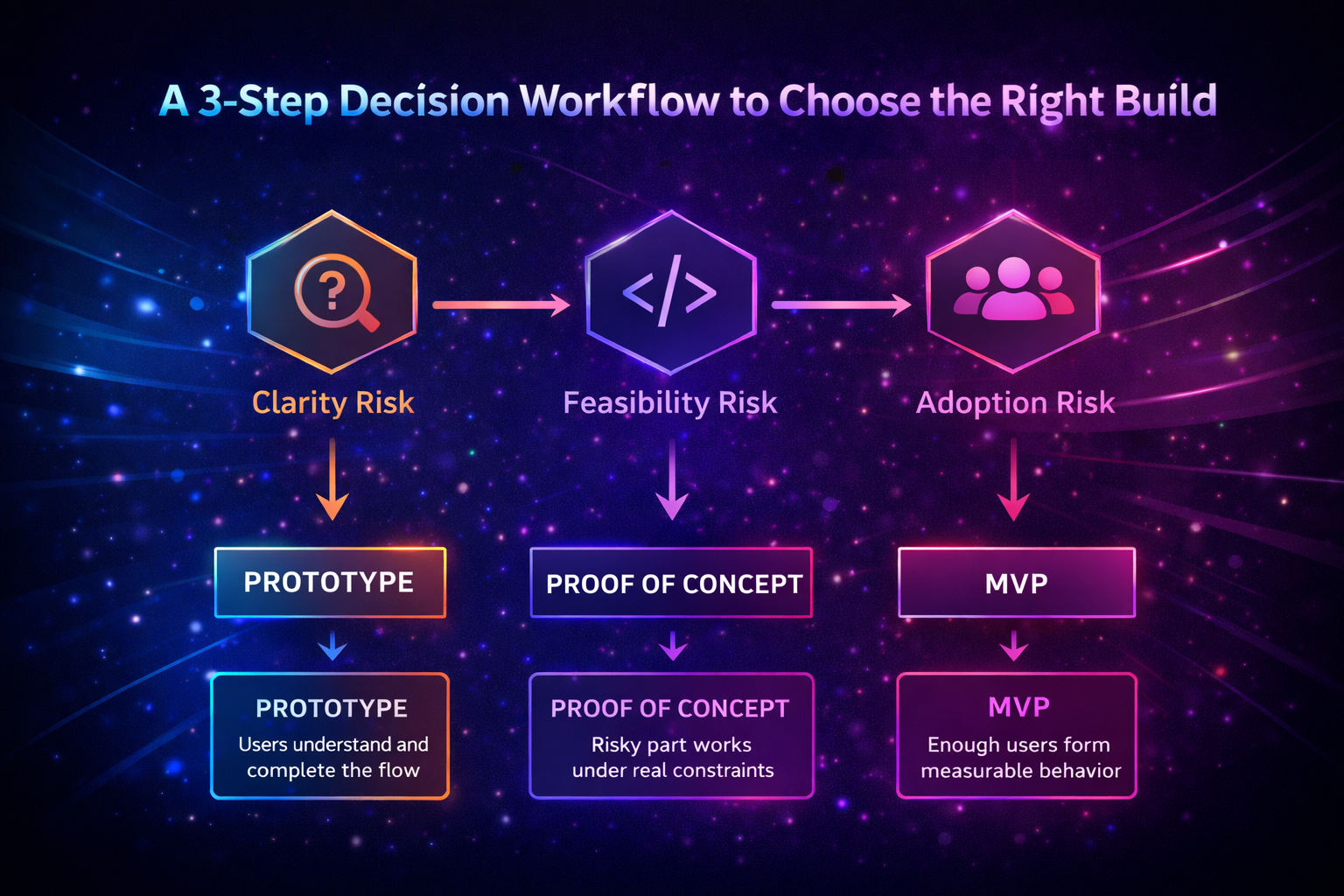

A 3-Step Decision Workflow to Choose the Right Build

Most founders don’t need another framework. They need a decision they can make in a few minutes without guessing. The easiest way to pick the right build is to match it to the risk you’re trying to remove. This is exactly what MVP vs prototype vs proof of concept is about, which is picking the right tool for the right uncertainty.

Step 1: Name the Risk You Are Trying to Remove

Start by choosing one risk only. If you pick two, you will build the wrong thing.

- Clarity risk

Users do not understand the flow, the value, or what to do next. - Feasibility risk

You do not know whether the hardest technical part can work reliably. - Adoption risk

You do not know whether people will use it without you pushing them.

This is where prototype vs MVP confusion usually shows up, because teams try to measure adoption before the experience is even clear.

Step 2: Pick the Smallest Artifact that Removes that Risk

Now decide what you need to build to answer the question, not what you want to build.

- If it is a clarity risk

Build a prototype that lets users move through the main journey and shows whether they understand it. - If it is a feasibility risk

Build a proof of concept that tests the riskiest technical piece with realistic constraints. - If it is an adoption risk

Build an MVP that lets real users complete one job end-to-end and produces measurable behavior.

Step 3: Define Success Before You Test Anything

This is what turns the exercise into a decision tool instead of a brainstorming session.

- Prototype success looks like

Users complete the flow without guidance and can explain the value back to you. - Proof of concept success looks like

The risky part works under realistic conditions, and you know the constraints to productionize it. - MVP success looks like

Users complete the core action and return without reminders, showing clear pull.

Real Examples Founders Relate To

A lot of advice on this topic stays theoretical, which is why teams still pick the wrong build and lose weeks. Real clarity usually comes from seeing how these choices show up in normal product work, not from memorizing definitions.

If you are comparing MVP vs prototype vs proof of concept, the examples below help you map each option to a real scenario and the exact question it is meant to answer. This also makes it easier to understand what is a prototype in practice, because you will see where it fits and where it does not.

Example 1: A Booking Product for Service Businesses

If your main question is whether customers will book without calling or messaging, a prototype helps you test the flow first. A clickable journey that shows selecting a service, choosing a slot, and confirming the booking will reveal where people hesitate.

A proof of concept makes sense only if the hard part is technical, like syncing real-time availability across multiple calendars without double bookings.

An MVP is the step where real users can complete a booking end-to-end, and you can measure completion and repeat bookings over the next week or two.

Example 2: A Marketplace

For marketplaces, the risk is often not the interface. It is whether supply and demand show up consistently.

A prototype can help you test whether users understand listings and filters. But many marketplaces start with an MVP that includes manual operations behind the scenes, because the learning is about behavior. You can ship a basic listing page, a search experience, and a request button, then manually match people to validate demand.

A proof of concept fits when the marketplace depends on a technical piece that must work, like real-time pricing rules, routing logic, or fraud detection that needs to perform under load.

Example 3: A B2B Workflow Tool

If you are building a tool for teams, the first question is often whether one team will use it weekly for one job.

A prototype tests whether the workflow is intuitive and whether the value is obvious without a demo call.

An MVP is one workflow, plus basic team invite and tracking, so you can measure weekly usage and repeat actions.

A proof of concept matters when the workflow depends on a risky integration, like pulling data from a system with messy formats or strict permission models.

Example 4: An AI Feature Inside a Product

AI products often fail when teams jump straight to an MVP without reducing technical risk.

A proof of concept should come first when accuracy, latency, or data availability is uncertain. You need to see whether the model can hit a usable baseline under real constraints.

A prototype can help you test how users want to interact with the AI, such as suggestions, automation, or chat, before you build the full experience.

An MVP is when real users can use the AI in one workflow, and you can measure whether it saves time, improves outcomes, or gets repeated use.

Common Mistakes Founders Make and How to Avoid Them

Most mistakes here happen because teams pick the right idea but the wrong format. They build something that looks impressive, then measure it as if it were built for a different purpose.

A common pattern is that the build gets judged by polish instead of proof. A prototype gets treated like market validation, a proof of concept gets treated like traction, and an MVP gets treated like a full product. The result is predictable. You collect the wrong kind of feedback, make the wrong decisions, and spend weeks improving the wrong thing.

The fix is to treat each stage as a tool with one job. A prototype is for clarity, a proof of concept is for feasibility, and an MVP is for adoption. Once you keep that separation, the mistakes below become much easier to spot and avoid early.

1) Calling a Prototype an MVP

What happens

Teams show a clickable flow, hear excitement, and assume they have validation.

Why it wastes time

You get opinions, not behavior. People can like a flow and still never use the product.

What to do instead

If you are unclear on what is a prototype, treat it as a clarity tool only. Move to an MVP only when the flow is understood without guidance, and the next question is adoption.

2) Using a Proof of Concept to Test Demand

What happens

The tech works, so the team assumes users will care.

Why it wastes time

Feasibility is not adoption. A working technical experiment does not prove the problem is painful or that users will switch.

What to do instead

This is where proof of concept vs MVP matters. Once feasibility is proven, design an MVP around one real job so you can measure usage and return behavior.

3) Building an MVP that Tries to do Too Much

What happens

Multiple personas, multiple workflows, extra settings, extra dashboards, all added to make it feel complete.

Why it wastes time

Your learning becomes noisy, and you cannot tell what drove the outcome.

What to do instead

Pick one user and one job. Keep the first release to one workflow end-to-end, then expand based on what users actually do.

4) Treating Compliments as Success

What happens

You hear “this is cool” and keep building.

Why it wastes time

Polite feedback does not predict usage.

What to do instead

Define success signals before testing. Completion of the core action, return usage, invites, or payment intent is stronger than praise.

5) Skipping Measurement Until Later

What happens

The product ships without clear tracking, and decisions turn into guesses.

Why it wastes time

You cannot prove what is working, so you add features hoping something sticks.

What to do instead

Track the core action from day one. Decide what result would trigger a change in plan.

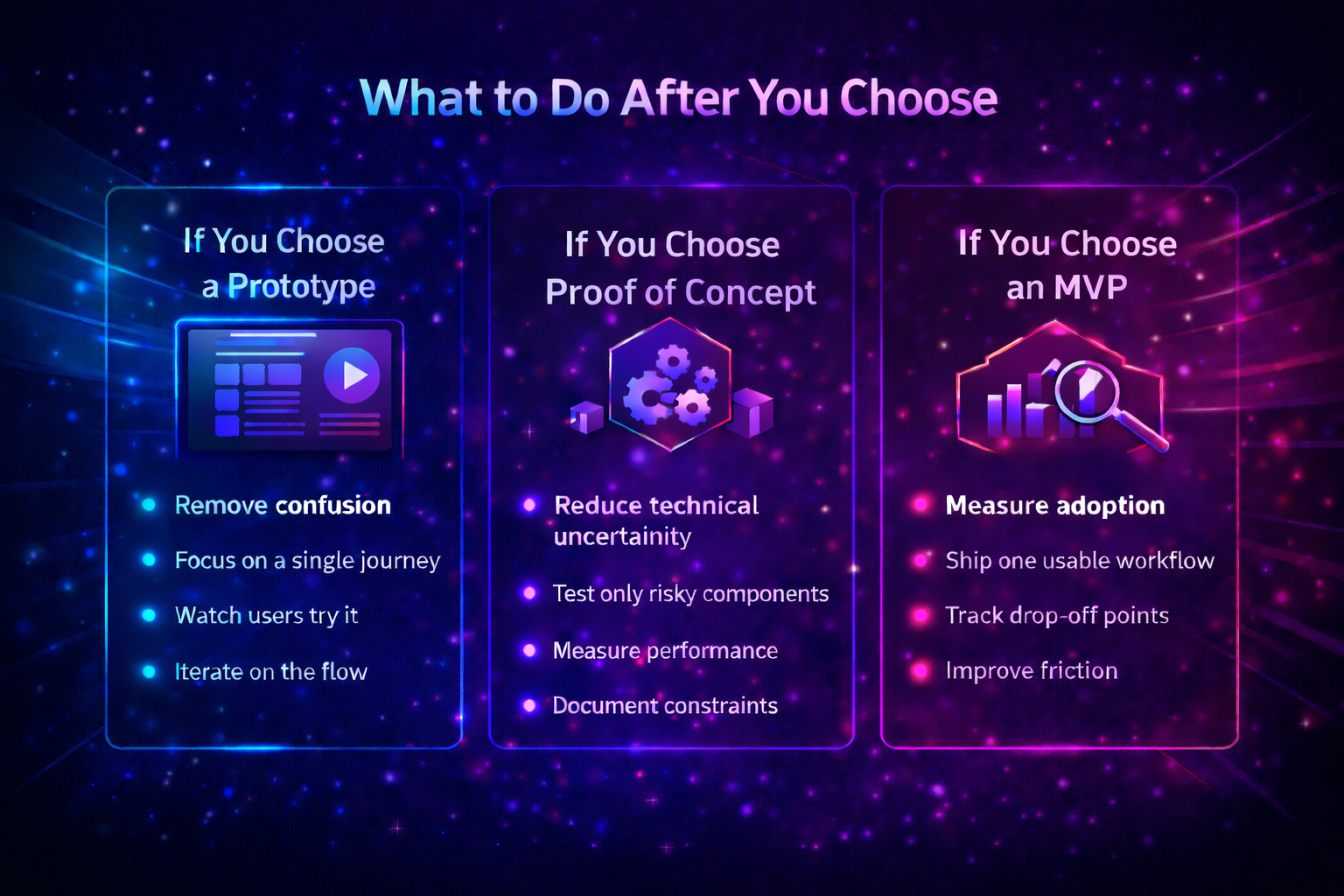

What to Do After You Choose

Once you pick the right build, the goal is to stay honest about what it is supposed to prove. This is where many teams drift. They start with a prototype, then add backend work and accidentally turn it into an MVP. Or they start with a proof of concept, then bolt on UI and start collecting feedback that the build was never designed to answer. This is the practical side of MVP vs prototype vs proof of concept, because the wrong next step can cancel out the learning you were aiming for.

Use the guidance below as a clean next step based on what you chose.

1) If You Choose a Prototype

Your job is to remove confusion, not to validate demand.

- Focus on one journey from start to finish

- Test with people who match your target user

- Watch them try it without explaining anything

- Iterate on the flow until they complete it naturally

When it is done, document what users understood quickly, where they hesitated, and what they expected next.

2) If You Choose a Proof of Concept

Your job is to reduce technical uncertainty, not to impress. This is where founders often mix up proof of concept vs MVP and end up asking users for feedback on something that cannot answer adoption questions yet.

- Test the riskiest technical piece only

- Use realistic data or realistic constraints

- Measure the critical performance or reliability threshold

- Write down constraints, trade-offs, and what production would require

When it is done, you should know whether the idea is feasible and what it will take to build it properly.

3) If You Choose an MVP

Your job is to measure adoption, not to polish the product. This also helps clarify prototype vs MVP, because the MVP must be usable end-to-end and produce measurable behavior, not just good reactions.

- Ship one usable workflow

- Track the core action and the main drop-off points

- Talk to users who completed the action and those who did not

- Improve friction before adding new features

When it is done, you should have a clear signal telling you what to build next and what to cut.

Conclusion

Prototype, proof of concept, and MVP are not interchangeable labels. They are different tools built to answer different questions. A prototype helps you test whether the flow and value make sense. A proof of concept helps you confirm that the hardest technical part can work under real constraints. An MVP helps you measure real adoption through usage. The fastest way to choose is to name your biggest unknown first, then build the smallest thing that removes it. If you want a second set of eyes on your plan, Novura can help you pick the right starting point and shape a build that produces clear learning instead of noise.

FAQs

Q1. What is the difference between an MVP and a prototype?

A prototype tests understanding and flow. An MVP tests adoption through real usage and measurable behavior.

Q2. Can a proof of concept be shown to users?

Yes, but only to explain the idea or gather early reactions. A proof of concept does not prove demand because it is built to test feasibility.

Q3. Which should come first, the prototype, proof of concept, or MVP?

Start with the biggest unknown. If the risk is clarity, prototype first. If the risk is feasibility, proof of concept first. If the risk is adoption, MVP first.

Q4. How long should each prototype, proof of concept, and MVP take?

A prototype can take days to a couple of weeks. A proof of concept often takes one to three weeks, depending on complexity. An MVP usually takes a few weeks to a few months, depending on the scope.

Q5. Which should I build first for AI products, a prototype, a proof of concept, or an MVP?

For AI, it often starts with a proof of concept to confirm accuracy and latency under real conditions. Then use a prototype to test how users want to interact with the AI. Build an MVP once you can ship one workflow end-to-end and measure repeat usage.

Q6. How do I know I picked the right one?

You picked the right one if it answers your biggest unknown with a clear result that changes what you do next.